Before we can explore the history of the Bridgeton Public Library, it is first important to understand the processes through which Carnegie granted money for the establishment of these libraries, and the wider social and cultural context in which this occurred. The history of the public library is interwoven with the growth of literacy, and other economic and social factors, which influenced the supply and demand of books. 1

The 19th century was characterised by social and political reform in Britain, fuelled by the height of the chartist movement. Chartism was a political movement rooted in the working-classes, dedicated to the reformation of the industrial and political order in Britain. 2 The group’s ideology centred around populism, in which they strived to represent those whose concerns were disregarded by established elite groups. 3 This meant fighting for the rights of the lower and working classes, and their new needs in the face of industrialisation. 4

Prior to the 19th century, library provision had taken the form of private and closed collections. A parliamentary return in 1885 indicated that only 8% of the population in Scotland were served by a public library. 5 However, towards the turn of the twentieth century, whilst books were still relatively expensive items, the ability for mass production meant that more individuals could readily purchase texts. However, many of these texts were still out of the reach of the working-classes. Thus, philanthropists began to invest in collections, acting as benefactors for the establishment of small local libraries.6 From here, collections and library buildings began to move towards an open-access model. However, much would still have to change before the public library as we know it today would come into existence. 7

It was the passing of the 1853 Public Libraries (Scotland) Act, which first awarded local burghs autonomy over the establishment of free public libraries. This act applied to all town councils which administered to a population of more than 10,000 people, creating an ability to levy a ½ penny rate of taxation, to provide for the accommodation and maintenance of a library. 8 This tax however could only be used for the provision of the library building, its upkeep and to hire staff- it could not be used for the purchasing of library materials. Thus, because of the financial condition of parts of Scotland at this time, many towns and local burghs could not utilise the scope of this legislation. For areas such as Bridgeton, the financial condition of the area meant that they were unable to take on the burden of a library without outside help.

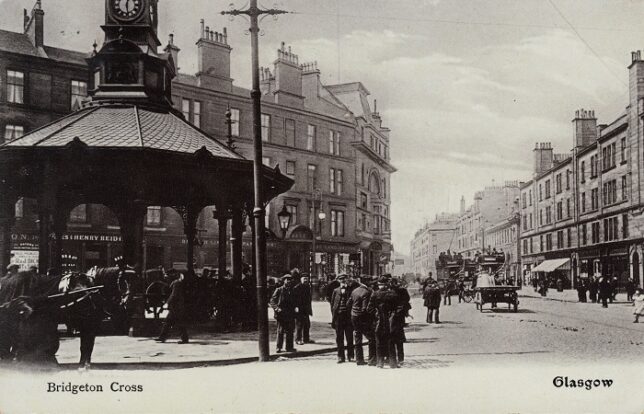

Lying on the outskirts of Glasgow, Bridgeton served as the heart of Scottish industry, with its industrial peak occurring between c.1870-1950. 9 The East End of Glasgow had evolved from a series of small villages, all of which had roots as weaving communities. It isn’t until the late nineteenth century that we began to see Bridgeton emerge as an engineering centre. Early industries were connected to weaving and textiles, but as the industrial power of Scotland swelled, Bridgeton began to expand dramatically into full-scale manufacturing. The area became world-renowned for its cotton weaving mills. Thus, a large population sprung up within the centre of Bridgeton, to support these industries. There were no less than 2,000 hand-loom weavers resident here during the 19th century. 10

Bridgeton now held a working population who devoted most of their time to industry, but who were soon to be the first to partake in new modes of working and leisure. Scotland began to move away from an agrarian economy at the turn of the twentieth century- an economy in which most people are working off or are profiting off the land, to a service economy. As we moved towards this new economic model, innovation within industry lessened working hours and thus, left workers with more free time than ever before. This then created a need for cheap and accessible entertainment for the working classes.

For many, an escape from the perils of industrial life was to turn to liquor, because of its cheapness and accessibility. As alcohol was deemed the ‘social evil’, the middle classes were eager to see that the working classes instead spent their new free time productively. Campaigners felt that encouraging the lower classes to spend their time advancing their prospects through self-education, would promote a greater social good. 11 In the background of this movement was the increasing proportion of the public who were now literate, because of the introduction of compulsory education in 1872, with the Education (Scotland) Act. The act required that all children between the ages of 5 and 13 had to attend school as a minimum. 12 Thus, public library provision grew to accommodate those who sought not only to educate themselves from their reading, but also to be amused and entertained outside of their working lives. 13

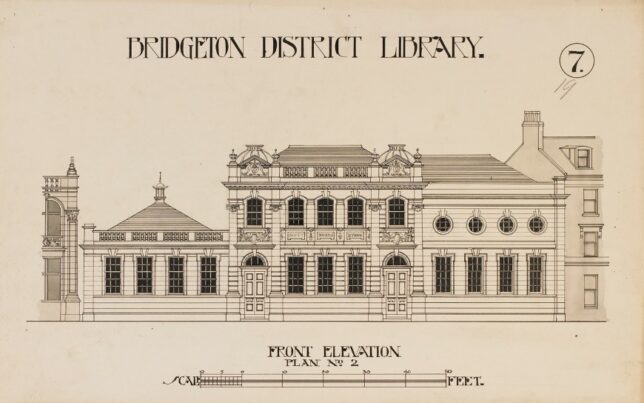

In 1901, Carnegie wrote to the Glasgow Lord Provost Sir Samuel Chrisholm to offer £100,000 to support the building of branch libraries in Glasgow, a donation which led to the building of libraries at Dennistoun, Bridgeton, Maryhill, Parkhead, Govanhill, Possilpark and Woodside, many of which still serve as libraries today.14 However, before the construction of these buildings was allowed to take place, the town would first have to prove their need for the grant money. Local authorities were required to demonstrate clearly that there was a need for a public library within the area, they also had to provide the site for the construction of the library and had to contribute 10% of the cost of this construction. Additionally, they had to prove that they could support the running costs of the library (which Carnegie very rarely contributed money towards). 15

The £100,000 of funding from Carnegie was given to the Glasgow Corporation at the end of the 19th century and was used to eventually build The Bridgeton Public Library. It was one of the first libraries that James R. Rhind designed, and it opened at 23 Landressey Street, in 1903.

However, now that the library was built, what good would it do for the people of Bridgeton, or more specifically the women of Bridgeton? As we will explore in the next blog post, the library was not designed for women to be at the forefront of its use. How then, did the women of Bridgeton whose lives were taken up almost entirely with their working and domestic duties, utilise this space?

For the next blog post in this series, follow this link- https://womenslibrary.org.uk/2021/09/15/the-women-of-industrialising-bridgeton/

References

1 – Chris Cardiff, ‘The Paradox of Carnegie Libraries: Must Libraries be Publicly Owned?’ (2001), https://fee.org/articles/the-paradox-of-carnegie-libraries/, page 2.

2 – The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, ‘Chartism: British History’, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Parliament.

3 – The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, ‘Chartism: British History’, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Parliament.

4 – Wikipedia, ‘Populism’, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Populism.

5- David McMenemy, ‘Public Libraries in the UK- History and Values’ (2018), University of Strathclyde,https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.cilip.org.uk/resource/resmgr/cilip_new_website/plss/l1_and_l2_ethics.pdf, page 6

6- David McMenemy, ‘Public Libraries in the UK- History and Values’ (2018), University of Strathclyde,https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.cilip.org.uk/resource/resmgr/cilip_new_website/plss/l1_and_l2_ethics.pdf, page 1.

7- Chris Cardiff, ‘The Paradox of Carnegie Libraries: Must Libraries be Publicly Owned?’ (2001), https://fee.org/articles/the-paradox-of-carnegie-libraries/, page 2.

8- David McMenemy, ‘Public Libraries in the UK- History and Values’ (2018), University of Strathclyde,https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.cilip.org.uk/resource/resmgr/cilip_new_website/plss/l1_and_l2_ethics.pdf, page 1.

9- Bridgeton Local History Group, ‘Bridgeton: Recollections From a Time of Change’ (2014), http://www.glescapals.com/blhg.htm.

10- Bob Currie, ‘Recollections of Bridgeton Past: A Personal Look back with 75 Year Old Bob Currie’ (2013), Glasgow, Clyde Gateway, http://www.glescapals.com/recollections-of-bridgeton-past-bobcurrie.pdf, page 5.

11- Wikipedia, ‘Public Libraries Act 1850’, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_Libraries_Act_1850.

12- Undiscovered Scotland, ‘Education in Scotland’ (2021), https://www.undiscoveredscotland.co.uk/usscotfax/society/education.html.

13- Neil MacDonald, ‘Carnegie Libraries of Scotland’, http://www.neil-macdonald.com/A2/intro.htm, page 2.

14- Kevan Smith, ‘A Carnegie Library in 2019, Glasgow Libraries’, (2019), https://www.cilips.org.uk/a-carnegie-library-in-2019-glasgow-libraries/.

15- Enrico Berkes and Peter Nencka, ‘Knowledge Access: The Effects of Canregie Libraries on Innovation’ (2021), https://static1.squarespace.com/static/584f190bf7e0aba029379a19/t/60f9ec96fdb29b40de67c2b0/1626991768813/berkes_nencka_carnegie.pdf, page 3.

Comments are closed.