‘From Scotland’s heather-covered braes,

In Babyhood he came,

And early fixed his childish gaze,

On lucre and on fame…//

So skilfully he flew his kite,

That wondrous was his luck;

He reached for all the cash in sight;

And rich investments struck;

At railroads, likewise coke and coal,

He took full many a fling,

And was cast at length for the glorious role

Of steel and Iron King//

His boodle grew at rapid rate,

But bitter was his cup,

So fast did the wealth accumulate,

He couldn’t count it up;

Of grief he might have died, they say,

If he hadn’t struck the plan

Of giving a few odd millions away,

Which made him a happy man.//

Of public libraries he spent

Of shekels not a few;

A godly slice of Pittsburgh went,

And to Allegheny, too;

But still the loss he doesn’t feel,

It cannot hurt his health,

For his mills keep on with endless zeal

A-piling up the wealth’.

Poem by Arthur G.Burgoyne, ‘All sorts of Pittsburghers, Sketched in Prose and Verse’ (Pittsburgh: 1982).

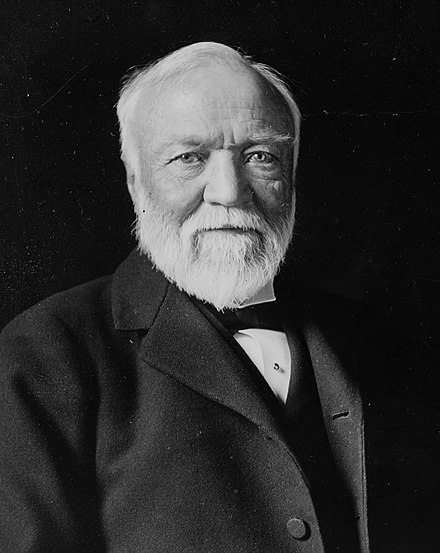

Such is the story of Andrew Carnegie, the self-made billionaire and philanthropist, universally celebrated for his contributions to the provision of education for all. Born in Dunfermline in 1835, to his father Will, a handloom weaver, and his mother Margaret, a seamstress, Carnegie hailed from modest circumstances. He received no formal education beyond a handful of years whilst living in Scotland and so, upon his arrival in Pittsburgh in 1848 following the migration of his family, Carnegie entered employment.

At first, he began his career in a cotton factory, and then as a telegraph messenger, before moving up the ranks to become the superintendent of the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1859.1 During this time, Carnegie largely self-educated himself through access to Colonel James Anderson’s personal library, using this knowledge to develop into one of the top industrialists of his time. 2 Carnegie began to invest his earnings and accumulating wealth into various industries, including steel, railroads, bridges, and oil derricks. 3 His wealth at its peak has been estimated to be around $300 billion in contemporary values.4

Now came the question of what to do with his fortune. Set out in his essay ‘The Gospel of Wealth’, it was Carnegie’s belief that the only solution to the inequality and unequal distribution of wealth which he himself had contributed to, was for, ‘The rich man to consider all surplus revenues which comes to him simply as trust funds, which he is called upon to administer for the benefit of the poorer brethren’. 5 Because of the extent of his wealth, Carnegie saw himself as the custodian of public good- he held the responsibility to administer his wealth for the benefit of the public, in ways he felt they could not or would not do for themselves. 6 To Carnegie, the most appealing expression of this custodianship of public good was the establishment of open-access libraries and investment into the education of the lower classes.

However, it is important to recognise that as an industrialist, it is likely that Carnegie used his philanthropical position to expand public education, in the interest of the success of his business. By providing these libraries, Carnegie was taking care of the wellbeing of those upon whose labour he depended for his success. This argument would certainly align itself with the new ideas of education which were becoming popularised at the time, whereby classical modes of learning were no longer the only option when it came to self-advancement. This meant that employers were now responsible for providing life and career-enhancing activities for their workers, allowing them to advance themselves through self-education. This may have been a way for Carnegie to ethically resolve his money. The library would be a legacy of his wealth, a way of paying tribute to the details of its accumulation. 7

Regardless of Carnegie’s motivations behind his investment, his choices changed the landscape of public library provision forever and created a new system of public entertainment and access to life-long education. His library grants started with a small number of cities, firstly in his hometown of Dunfermline, but quickly became an international phenomenon. At the time of his death in 1919, there were more than 2,500 Carnegie libraries, many of which were built in his home country. It is this point which marks the beginning of the Bridgeton Public library- the beautiful building in which our organisation is now situated.

My name is Erin and I am a fourth-year archaeology student at the University of Glasgow. As part of my work placement with the Glasgow Women’s Library, I have researched the processes through which Carnegie invested in libraries across the globe, and how the Glasgow Women’s Library came to occupy one of these spaces. I have presented this research in the form of a series of blogs, which can be found at: https://womenslibrary.org.uk/tag/erincarnegieseries/.

Through these blog posts, we move beyond a discussion of the library as solely a public institution, to investigate its role in the lives of Bridgeton’s women throughout time. By contextualising the library’s use within wider social and economic contexts, we can begin to unfold to what extent the library has met the needs of the women of Bridgeton across time, and how the way in which women have occupied this space has changed.

For the next Blog Post follow this link- https://womenslibrary.org.uk/2021/09/14/the-origin-of-the-public-library/

References

1 – History.com, ‘Andrew Carnegie’ (2021), https://www.history.com/topics/19th-century/andrew-carnegie.

2 – Chris Cardiff, ‘The Paradox of Carnegie Libraries: Must Libraries be Publicly Owned?’ (2001), https://fee.org/articles/the-paradox-of-carnegie-libraries/, page 3.

3 – Wikipedia, ‘Andrew Carnegie’, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andrew_Carnegie.

4 – Wikipedia, ‘Andrew Carnegie’, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andrew_Carnegie.

5 – Paul L. Krause, ‘Patronage and Philanthropy in Industrial America: Andrew Carnegie and the Free Library in Braddock, PA’, The Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine, vol 71 (1988), https://journals.psu.edu/wph/article/view/4104, page 132.

6 – Andrew Carnegie, ‘The Gospel of Wealth’, Bedford, Applewood Books (1889), https://www.carnegie.org/about/our-history/gospelofwealth/, page 4.

7 – Paul L. Krause, ‘Patronage and Philanthropy in Industrial America: Andrew Carnegie and the Free Library in Braddock, PA’, The Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine, vol 71 (1988), https://journals.psu.edu/wph/article/view/4104,page 120.

8 – History.com, ‘Andrew Carnegie’ (2021), https://www.history.com/topics/19th-century/andrew-carnegie.

Comments are closed.