We queer things when we resist the regime of normal: the normative ideals of aspiring to be normal in identity, behaviour, appearance and relationships.

-Michael Warner Trouble with Normal, (1999)

Queer: A Graphic History, is a book by cartoonist Julia Scheele and Activist-Academic Meg-John Barker. It is both complex and simple, informative and questioning, funny and deep. It even manages to make those like theorists Michel Foucault and Judith Butler easy to understand if you’ve struggled in the past to get by their terminology!

I wish this book had existed when I was a kid figuring out stuff about myself. Born in 1993, I was of the generation who wasn’t fluent in the internet as the next generation would be. Instead we occupied the space between BI(Before Internet) and AI(After Internet). I learnt about stuff like menstruation, bullying and puberty from books found in Borders, Buchanan Street(R.I.P) not websites. Going to a Catholic high school our sex ed left much to be desired, and it took me years to recognise it hadn’t really mentioned gender identity and sexuality. I know many people who only learnt they were LGBT+ after they left the school. I was one of them. I soon understood I was non-binary and asexual(although now I more align with bisexual). I wish this book had existed. And that my school would have used it to teach us about the complexity, beauty and variability of gender and sexuality. But that didn’t happen.

The art by Julia Scheele cannot be praised more, Scheele’s art and Barker’s words come together seamlessly to get across, often very complicated, concepts and engage the reader via the comic medium. They are a dream team.

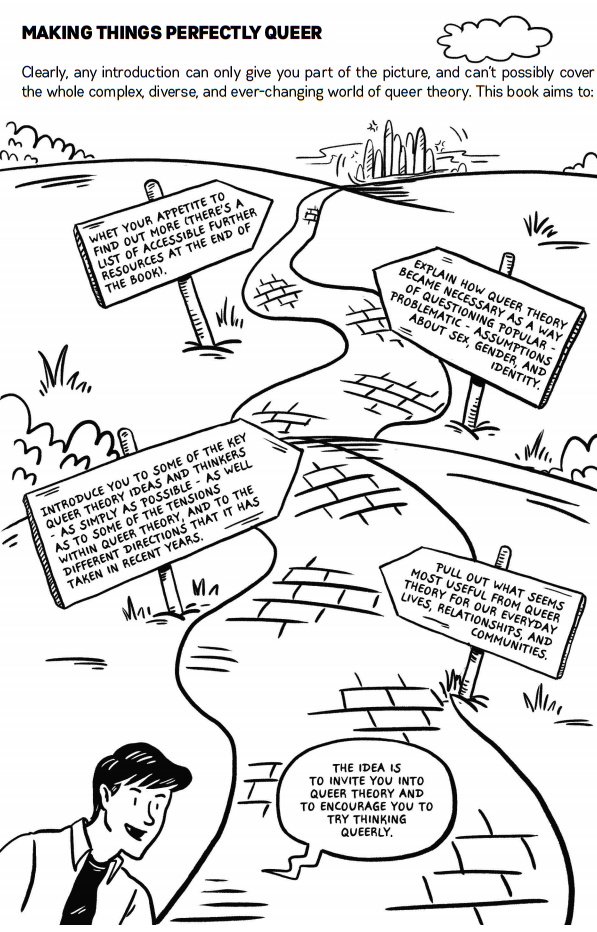

Barker sets out the aim of the book as introducing us to key queer theory ideas, thinkers and tensions. It’s to help act as a gateway to further reading. It explains why queer theory is needed and how we can use it to understand our lives. Queer is many things she argues. It has, like gender and sexuality in general, been molded by context. Originally it meant weird, then it became a homophobic insult ,but since the 1980s a substantial part of the LGBT+ community have reclaimed it. This doesnt mitigate the fact it often has connotations of abuse and harassment for LGBT+and consequently should be used with consideration, she adds.

Barker calls the main idea of Queer explored in the book, Queer as a verb. By Queering things, as Warner mentions above, we resist the normal. It’s a revolutionary act. We see the power structures and operations in society and culture that impact us all and highlight them through our rebellion. Like Gender studies, Queer studies goes beyond non-heteronormative identities and wants to encompass all sexuality into research that considers how everyone is shaped by these concepts and identities. Through Queer theory, resisting categorisation, challenging essentialism(that we are essentially something at our core). questioning binaries, demonstrating the contextual nature of sexuality and gender and examining power relations can occur.

As someone in history whose focus is disabled history, its great to see Barker go into detail on how sexuality and gender is contextual. It is dependent on the time and place we are in. The understanding of sexuality held by ancient Greeks, 18th century citizens and modern people is going to differ. They cite the example of masturbation being seen as a dangerous psychological problem in the 19th century called Onanism.

In an amazing main section of the book, Barker, with Scheele’s fantastic artwork, manages to distill the theories of many theorists whose impact on Queer theory has been considerable. The Existentialists like Camus, Simone de Beauvoir, Sartre and Merleau Ponty feature who denied essentialism stating “existence precedes essence”. This means we can be what we want with set essential social and biological identities just means of constraint. Beauvoir however pointed out for marginalised groups this freedom was not so simple with The Second Sex stating, that women are in a state of becoming not being. Despite this they often feel the need to become “for-others“-women made for men, the dainty girl, desirable woman, the mother and wife.

The work goes on to consider Simon and Gagnon’s sexual script involving sexuality as something developed between culture, relationships and our inner self. Bem’s concept of androgyny, that gender isn’t innate is highly relevant today. She suggested that we should “Let 1000 categories of sex/gender/desire blood. Through that proliferation we can undo the privlidged status of the two and only two categories as normal and natural.” With a modern world in which non-binary identities are increasingly common, humanity might be slowly working towards Bem’s idea.

Barker then explores black theorists like Audre Lorde and Bell Hooks, who saw the failure of the civil rights and feminist movements in representing the intersectional identities and particular issues that black women deal with. She quotes Hooks statement that “understanding marginality as place of resistance not despair” is fundamental for holding “people accountable for wrongdoing” and potentially transforming these individuals.

As seen by examples like, Barker’s discussion of Adrienne Rich’s Compulsory Heterosexuality, she isn’t afraid to both acknowledge a theorist’s important and give criticism where it is warranted. Compulsory Heterosexuality is an important idea, but Rich’s binaries of women in relationships with men as coercion and women with women as political, alongside her exclusion of Gay and Bi men, are not things that should be ignored.

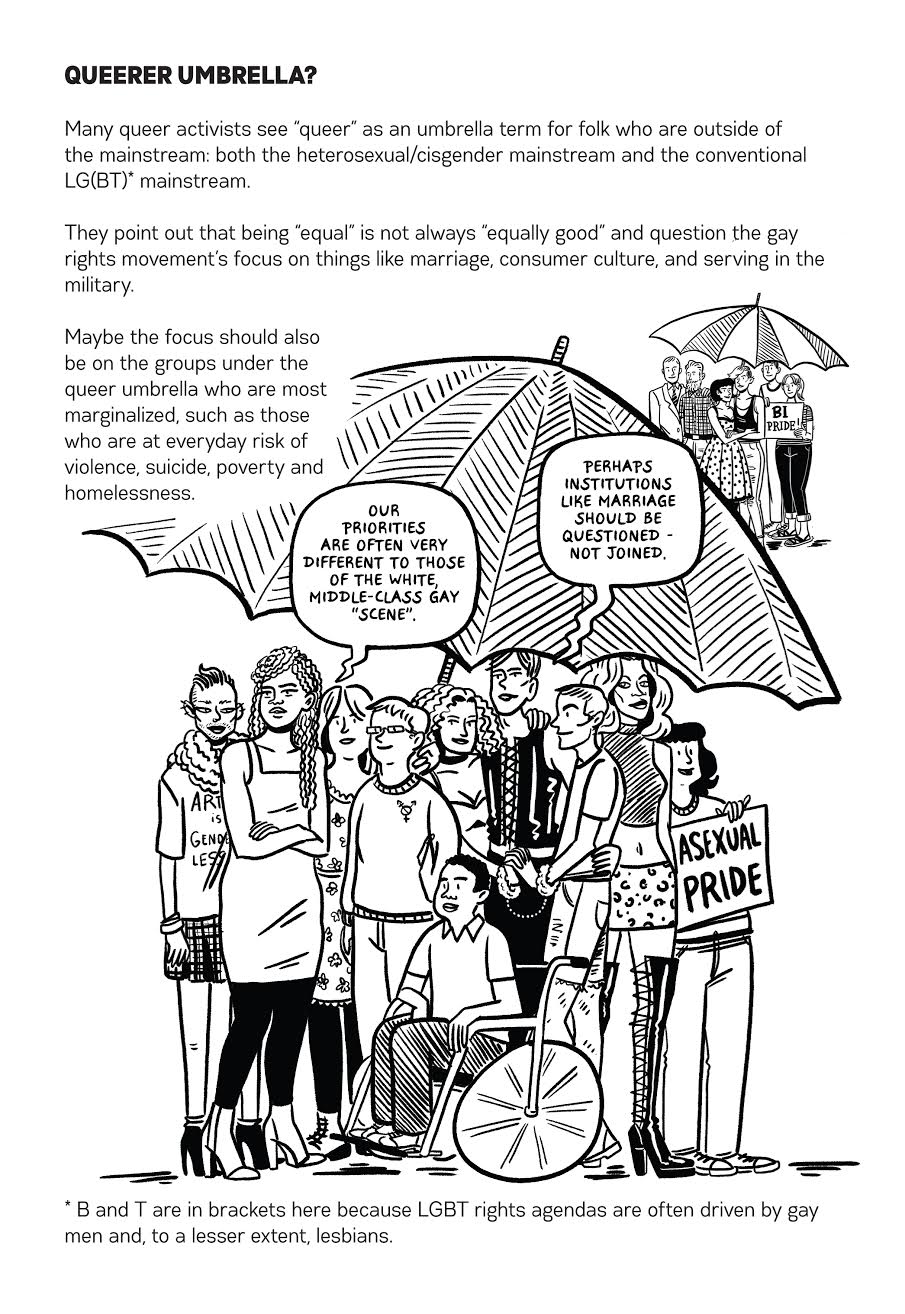

As well as a history of theory and thinkers, Barker brings us up to date looking at Crip theory, the exclusion of Bi and Trans people in LGBT+ communities and Kimberle Crenshaw’s intersectionality. This posits that not one axis of oppression is separate from others instead identity is interactional, hierarchies don’t exist and identities are impacted by power relations. Barker fails to mention however that Crenshaw developed the idea as a concept pertaining to black women’s experiences. The fact its been divorced from its context in 2018 is worth considering.

All in all, Queer: A Graphic History, like the concept it considers, refutes and evades categorisation. It’s a fantastic comic and text. Beautiful Art and words. A book that is a perfect introduction to Queer studies/theory/activism and by extension gender and sexuality. A book that can revolutionise the experience of someone just figuring out their gender and sexual identity at school or teach something new to those who are older. Check it out in our loaning library!

Comments are closed.