As part of my Gender Studies Masters degree at the University of Stirling, I’ve been given the opportunity to carry out a research placement within the GWL archives, examining the Edinburgh Women’s Liberation Newsletters. As my project continues, one of the most fascinating aspects has been looking at the way Edinburgh feminists used the newsletter as a means of expressing opinions on a wide range of issues. Today marks the 32nd anniversary of the Chernobyl disaster, and it is clear from the newsletter issues following the disaster that the feminist movement in Scotland was concerned with the impact of an ecological pollution event on this scale. It is massively beneficial to have documents which give the reactions of contemporary observers to notable events, particularly ones which have a continued impact, such as Chernobyl.

In terms of my project, I have been trying to identify the issues that the Edinburgh feminist movement were most concerned with, and the scope of their activism was broad. From the very beginning of the newsletter in 1974, there is a clear sense of common struggle and solidarity with women and feminists in other countries, and in this case, there was a considerable overlap in local and global activism as the pollution spread across Europe and the threat posed by the disaster became clear.

Looking at the Chernobyl-related content in the newsletter in the months after the disaster in April 1986, what becomes clear is not just the depth of concern but the scope of issues that were raised by this one event. For example, the July 1986 issue of the newsletter features a wide array of responses to the accident, from poetry, written by Elizabeth Burns and Linsay Stevenson, to reviews of books about the effects of radiation.

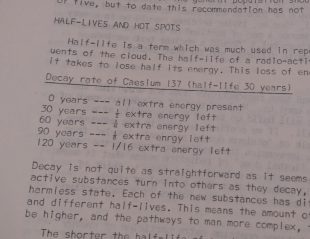

In an article entitled ‘Learning to live with the nuclear age’ – a longer version of an article published in the Scotsman – journalist Sue Innes explores the impact of the disaster within Scotland, and the corresponding public response. As she notes, “for most of us this is, however limited, our first direct experience of what living in the nuclear age means”. This meant that politicians and government agencies were as ignorant as the public, and were unable to give helpful advice on what, if any, safety precautions were needed. Added to this, the circulation of conflicting information from scientists and experts caused even more frustration. Innes argued that this response was less hysteria and more an awareness of the effects of radiation on the human body coupled with a lack of trust in the government’s ability to be transparent about the potential harm, particularly to children, that the disaster could lead to.

There are also reports of political activism carried out in response to the incident. There was a protest on July 5th at the site of Torness Nuclear Power Station, which was under construction at the time and would be commissioned two years later in 1988. This demonstrates the fears of locals that a disaster like Chernobyl could happen in Scotland, and that if that were to happen the emergency services would be unprepared for something on that scale.

The response of the Edinburgh feminist community to the Chernobyl disaster continues to feature in the newsletter in the following months, and this serves as a valuable resource for those seeking to examine contemporary perceptions of nuclear power and the Cold War.

Comments are closed.