by Zefi Kavvadia

As part of my placement here at the Glasgow Women’s Library, I have had the opportunity to get my hands literally on anything I wanted (admittedly, I have used this opportunity to get my hands on a lot of Scottish shortbread biscuits and leftover food – sorry!), from attending important meetings and working with different ongoing projects, to library work, participation in events, and archival research and training. One of the most exciting projects for me, and probably what I most looked forward to upon arriving from Greece to volunteer at the library, was the Lesbian Archive. Partly academic and partly personal, my interest was well-received. Working with Alice Andrews, project co-ordinator for the Lesbian Archive, and several fantastic, wonderful, and awesome volunteers, I discovered that the archive was home to Lavrys, the first and arguably the only Greek lesbian feminist publication till the mid-1990s.1 As I am, for now, perhaps the only person at GWL able to decipher the Greek alphabet, I guess this was almost a calling!

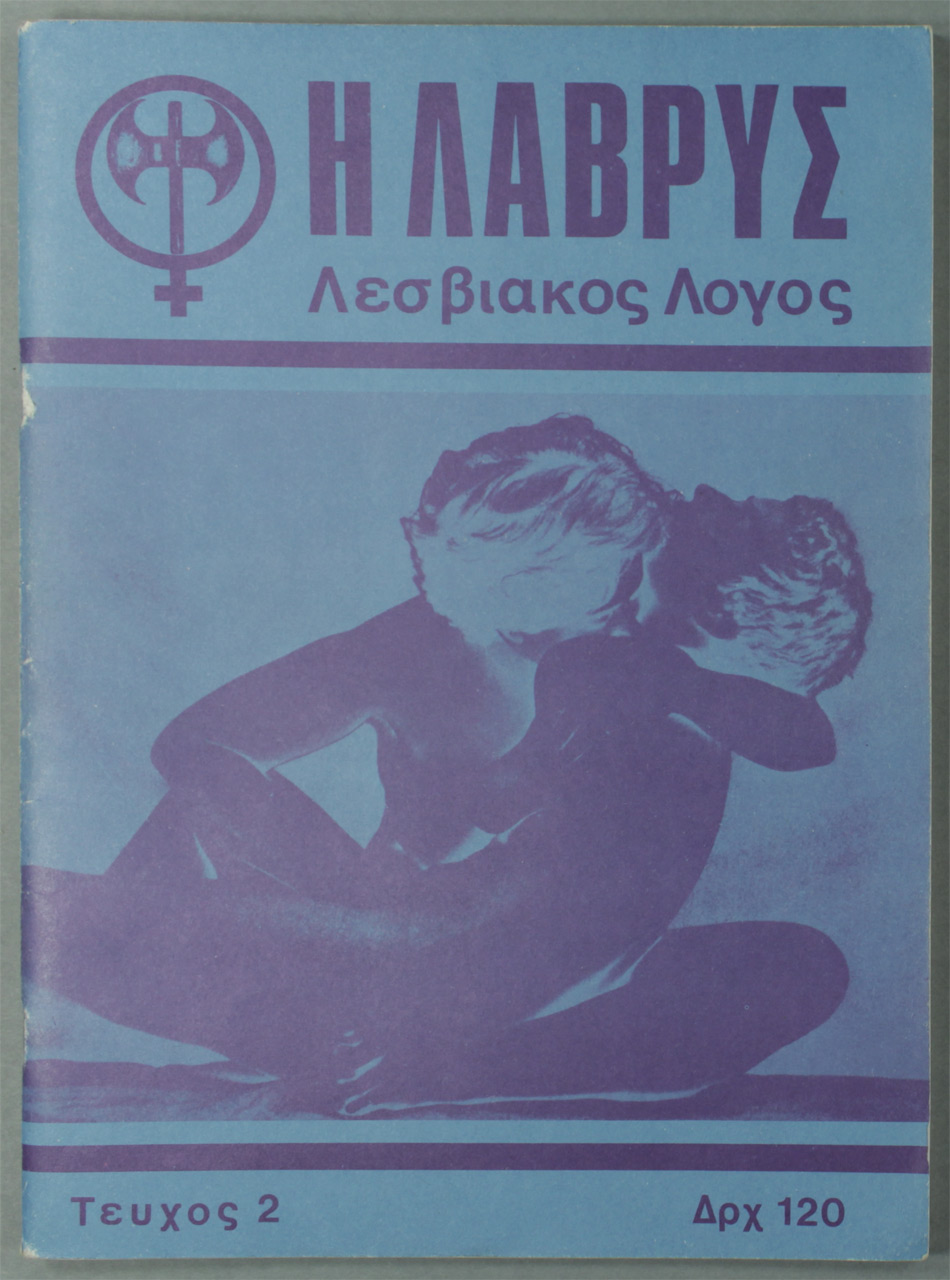

Lavrys (in Greek, “η λαύρυς,” i.e. “the labrys”) was first published in March 1982 by a group called Autonomous Group of Homosexual Women (Αυτόνομη Ομάδα Ομοφυλόφιλων Γυναικών), based in the Women’s House, a grassroots feminist centre focusing on bringing Greek women together and speaking out in support of women’s issues. Members of the Autonomous Group were previously members of the Greek Homosexual Liberation Movement (Απελευθερωτικό Κίνημα Ομοφυλόφιλων Ελλάδας/AKOE). After a series of disagreements with the male members of the group over the latter’s perceived negligence of feminist politics, these women joined the feminist-affiliated Women’s House and embarked on the effort to produce what they called “women’s speech and dispute”.2

The magazine only managed to publish three issues, but it is to this day one of the most important documents for Greek lesbian politics, Greek feminist politics, and their intersections. In the cultural climate of the late 1970s and early 1980s, feminism found a relatively fertile ground to grow in Greece, albeit only for a short period of time. After a seven-year totalitarian dictatorship of ultra-right wing militarists, the state was undergoing a kind of “socialist change” that saw work conditions improve, the democratization of education, and leftist ideologies, as well as the people supporting them, finally taking up influential positions. In this context, young Greek queer women who had studied in European and American universities, and had witnessed the surge of various oppositional politics, attempted to import the ideas they had embraced into the changing Greek society, familiarize Greek lesbians with radical feminism, and connect lesbian feminism to other struggles.

Lavrys makes reference to the frustration these women felt when they tried to locate lesbian culture in Greece: “To this day, Lesbian speech has not been heard in our home, and this is a great gap that today, in 1982, cannot be excused.” It is true that feminism, and especially lesbian-identified feminism, has had a hard time catching on Greek society. This is largely due to the fact that most communities, and especially the ones outside the capital, are still organized with kinship and marriage at their heart – gender roles and gender expressions are policed in the Greek countryside and small towns, with the aim of preserving what is thought to be traditional, familial values.

In this context, the contributors to the magazine tried to first familiarize readers with what had already been pretty much established lesbian feminist and radical feminist writing: translations of Adrienne Rich’s “Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence” and Of Woman Born appear alongside Janice Raymond’s essay on “gyn/affection,” as well as poems and essays by activists, for example from the American lesbian feminist magazine Sinister Wisdom. It feels to me that the writers and translators (who, for the record, remained mostly anonymous by using just their first names) made an admirable attempt to situate almost exotic ideas to the Greek context, bringing up examples from everyday life or using fairly standard, accessible language.

The issue of communication, and accessible communication for that matter, is a very important one for Lavrys, and this is highlighted by the various reports from lesbian and feminist groups around the world, as well as an extensive correspondence column (in which one reader asks whether it’s possible to exchange letters with the writers just for chit-chat, and actually gets a positive answer)! From the very first issue of the magazine, it is clear that these women find the lack of communication and of a common discourse to be the most important obstacles for lesbian women in Greece.

In my opinion, the most interesting aspect of the magazine, which relates to communication and the formation of community, appears in the third and last issue. In this issue there is a series of articles covering the participation – or more appropriately, intervention? – of the group publishing Lavrys in a conference organized by the high-profile Greek queer magazine AMFI in November 1982. Scholars like Felix Guattari and Wilhelm Kempf attended, as well as emerging Greek psychoanalysts and journalists; at some point in the conference, several women stood at the podium and made a speech deriding the elitism of the movement, the one-sidedness of communist and Marxist perspectives that asked for women to wait for class emancipation first, and the gay men, too absorbed in their privilege to look beyond sexuality as a source of oppression. The speech ended with the phrase “The future is female,” and set the stage for a series of internal arguments that kept the Greek LGBT movement immobile for several years. In this last issue of the magazine, it is becoming apparent that Greek lesbian feminists are realizing that gender, sexuality, and class intertwine in very complex ways, and that alliances in the struggle for rights and liberation are often ephemeral.

While there are certain features in the magazine considered today as more problematic, for example the focus on lesbian-identified women rather than the inclusion of non-straight women in general, the reproduction of the work of more controversial writers like the radical feminist Janice Raymond mentioned above, and a latent essentialism in what they considered to be women’s “nature,” I believe Lavrys was an honest and successful attempt at introducing lesbian feminism in Greece. And while things have certainly improved, it is unnerving and at the same time encouraging that its calls to action, its analyses and its sensibilities are still relevant.

1) Madam Gou was published from 1995 to 1997, but the magazine was not outwardly political in any way. The next Greek periodical publication to appear which has focused on lesbian identity, culture, and lifestyle, Ntalika (meaning “lorry,” a re-appropriated derogatory term used against butch women) has been published since 2009.

2) The first issue is subtitled “γυναικείος λόγος και αντίλογος”, which roughly translates to “women’s speech and dispute”, a testimony to one of the first attempts at radicalizing lesbian experience and discourse in Greece.

—

Return to Feminism and Lesbian Politics or the LGBTQ Collections Online Resource.

—